We caught up with Whipstitch curators, Thea Augustina Eck and Rachel Anna Walker to get their thoughts on the curatorial process, textiles and technology and surprising moments in putting together the show.

What’s the story behind this exhibition?

Thea:

I wanted to do a show at the [Ann Arbor] Art Center that featured new media and artists working with different digital technology in their practice. I work in the field of digital technology and digital fabrication; Rachel works as a commercial textile designer. We decided to team up to and artists who are utilizing digital technologies to produce and/or inform their work. For example, textile artists that are coming from a traditional method, such as weaving and hand embroidery, are now using digital tools to enable them to work faster and broader, expanding their visual language. I also wanted to introduce new ways of making and seeing textiles to the Ann Arbor community.

Rachel: Thea made this show happen, it was her original idea, and I was so happy to get on board. Thea was like, “‘I have this idea for a textile show.” Thea is an incredible artist and has a lot of experience working three-dimensionally, as an installation artist, and also as a technician. I’ve always admired her and her work so I was really excited to do this with her.

What is the difference between weaving, embroidery and quilting?

Rachel: Weaving is a method of textile production in which two distinct sets of yarns or threads are interlaced at right angles to form a fabric or cloth . Embroidery is stitching on fabric. It’s always been considered decorative and typically uses colored yarns to create marks on fabrics. One of the artists in the show, Rebecca Ringquist, likens it to drawing or painting with thread. Traditionally it’s a much more rigid medium. Quilting is typically two to three pieces of fabric stitched together to create a thicker quilted fabric.

How do textiles and technology intersect?

Thea: The textile industry has always been innovative in finding new ways to create. From the cotton gin to digital looms. At the same time, the fine art world has always sought out and incorporated the the modern innovation at the time. Today, even musical instruments can be made using CNC technology. All the artists in the show have a firm grasp of traditional craft, but have made a conscious decision to integrate digital technology into their work whether to expand what their own practices, or for their own curiosity, or both.

Rachel: The practice of making textiles is ancient. The first looms were very crude wood frames. But as technology advanced and evolved so did the making of cloth. During the Industrial Revolution the first steam-powered mechanized looms were invented. In the early 1800’s the jacquard loom was developed. Jacquard was a french weaver who figured out how to program a loom to weave complicated patterns in a repeating sequence, which is the foundation of modern computing and programming. There’s a direct line between the punched card system Jacquard developed for his loom and the founding of IBM. So now today, we have artists like Libs Elliot creating quilting patterns generated by computer code. Or Ohne Titel using 3D printing technology to create fabric. It’s really excited to see how textiles and technology continue to inform each other.

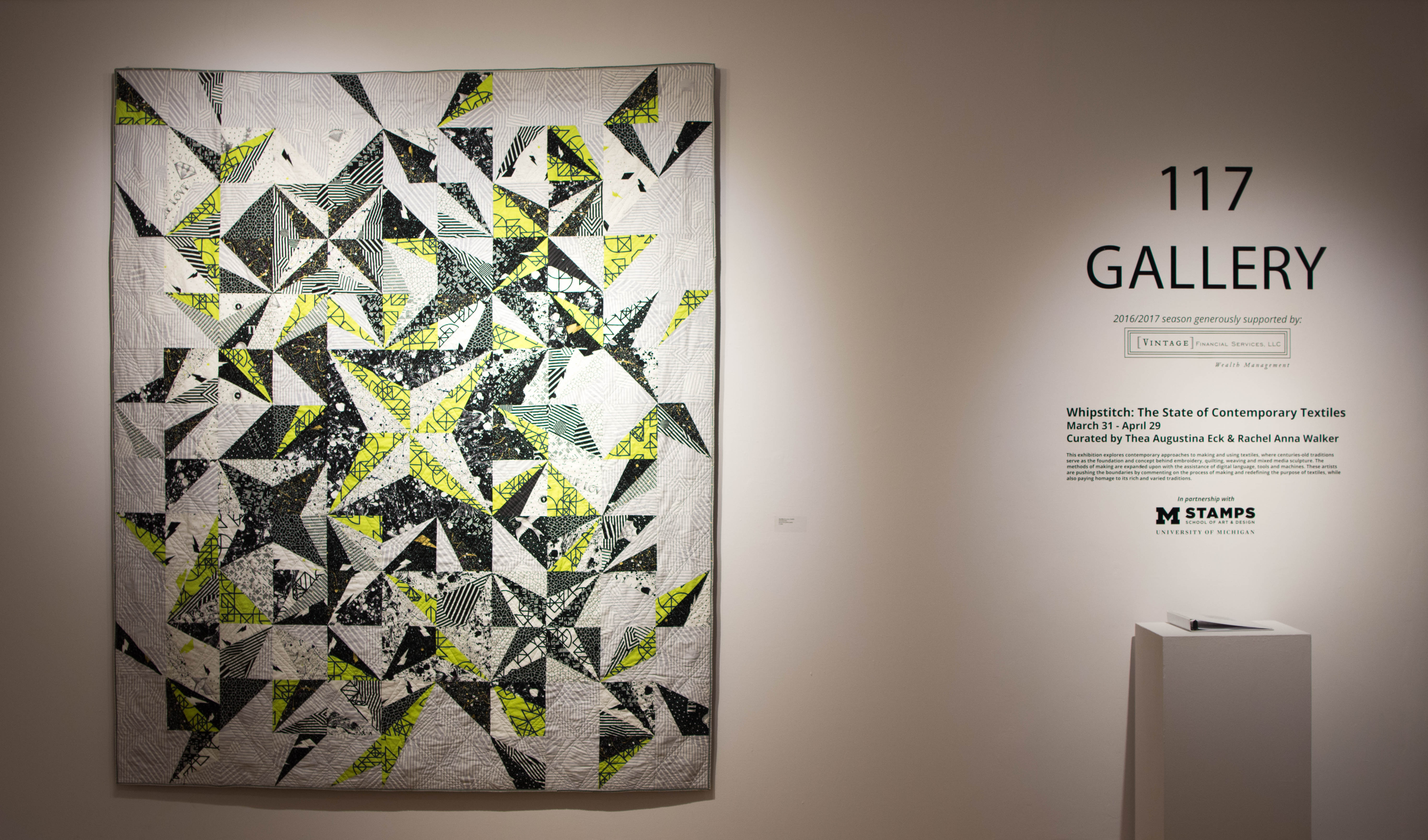

Exploding Stars, by Libs Elliot

What was the most surprising moment of the curatorial process?

Thea: One of the surprising moments for me was just to see how gracious the artists have been. This show is a blend of emerging artists as well as mid-career artists and that was really important to me when curating the show to get a range of artistic experience. I’m really excited to have Alexa Adams and Flora Gill’s 3D printed dress. It’s a beautiful example of digitally printed cloth, that has then been hand crocheted together to make an object that is both functional and lovely to look at. It also reflects the thesis of our show, the marriage of handcraft and technology.

Rachel: I didn’t know what to expect really. This was the first time for me, co-curating a show. Thea and I are friends with some of the artists, but some of them we only know from researching their work online. We hadn’t seen many of the pieces in the show in person, so when you finally see these works up close it’s really wonderful. Embroidery for example, you can’t have a sense for it until you see it in person because it’s a three-dimensional thing. The amount of hand craftsmanship that goes into it, the vibrant color of the thread, or the stark contrast of white on black, the movement of the fabric… it’s just something you have to experience in person to really understand and appreciate.

Ohne Titel- Flora Gill & Alexa Adams Finale Dress

How is Whipstitch related to the contemporary art world?

Rachel: Textiles is an integral part of contemporary art. It’s not a coincidence that all but one of the artists in this show are women. For centuries, textiles, weaving, embroidery, quilting were deemed women’s work, purely decorative and not taken seriously as an art form. Without getting into a larger conversation about feminism and discrimination, contemporary art practices have been redefined to include decorative arts, installation, and performance—and textiles is a huge part of that. The craft, technology, and traditions of textiles have been co-opted by artists to tell their stories and explore their identities and the issues of today.

Why should people come see Whipstitch?

Thea: Whipstitch represents artists whose work investigates craft through the lense of new media and digital technology and how those two collide. It’s much more powerful to see a work of art in person as opposed to on our computer screens or as an image in a book. When you see textiles up close, you can see the beautiful imperfections of hand stitching, and also the remarkable craftsmanship and control, you see the textures, it’s illuminating and inspiring. The level of detail that’s involved in making this work is incredible and you must see it to truly comprehend it.

Rachel: The craft, the tradition, and the expertise involved in making these items is really quite extraordinary.Textiles are so personal, they’re human scale and often for the body, or for a place your body inhabits, a bed, or a couch, for example, and so it’s impossible to not connect to these works in a personal way. These textiles are three dimensional and they are surface; they are functional and they are conceptual; they are handcrafted and machine made, this was the tension and the beauty we wished to explore with this show and we hope people will come to see it.

See more images of the artwork in Whipstitch